Muharram in the Walled City of Lahore

Muharram is the second holiest month of the Islamic calendar, after Ramadan. For many it is a time of solemn reflection, but for the Shia it is a period of intense mourning. It was on the 10th day of Muharram (known as Ashura) in the year 680AD that the grandson of the prophet Muhammad ﷺ, Hussain, was murdered along with around 100 of his family and companions at Karbala in Iraq.

Lahore is home to a significant percentage of Shia who mourn the events at Karbala, creating a spectacle of faith and grief that is beyond anything I’ve ever experienced. And so it was that I found myself in Lahore this year during Muharram, camera (and camera phone, for those discreet shots) in hand, ready to capture the incredible scenes as they unfolded before me.

Before I go any further, I think it’s important to note that the mourning of Muharram is a highly emotive and sensitive topic for many, whether they mourn or not. I request that anyone reading this continues with sensitivity and an open mind. The aim of this post is not to advise on the theological aspects of mourning, nor is it an advertisement of any sort – it is simply a reflection on what I witnessed.

If you are offended or triggered by stories about Muharram processions, or if you are squeamish to the sight of blood and graphic mourning rituals including self-flagellation, I advise you to go read something else like this.

I arrived in the Walled City of Lahore on the 3rd of Muharram, just as the mourning was getting underway. It’s actually a ten day event, and much longer if you count the mourning anniversaries which extend out for another two months more. I was travelling with a good friend of mine, and he was guiding me as we navigated the city.

Our first stop was Nisar Haveli, a beautiful old mansion that plays host to a majlis, or religious meeting, each night of the mourning. We took a seat at the side and listened in, as the aalim (preacher) began to relate stories of the greatness of the family of the prophet Muhammad ﷺ. As his claims grew bigger and bolder, the crowd began to cheer – occasionally breaking into a cry of “Ya Ali!”, an exclamation of admiration for the son-in-law of the the prophet Muhammad ﷺ, a key figure in Islam.

Nisar Haveli, Lahore

The congregation was divided between men and women, but everyone had a clear view of the aalim. After about half an hour the tone changed dramatically, as the masaib began. This is the part of the majlis where the preacher begins to tell the story of the tragedy at Karbala, and suddenly there was no cheering or whooping, but instead quiet tears and sniffling. As the story led up to its climax, the tears exploded into loud cries; some men and women in the crowd began slapping their folded legs, thumping their chests, or hitting their heads, seemingly finding a way for their deep sorrow to escape. The aalim was also becoming emotional – shouting, gesturing, painting a picture so vivid that it was impossible not to be moved.

By the end, the entire congregation was awash with tears. Stories like that of Ali Asghar, Hussain’s six month old son, who was shot in the neck by a hunting arrow. Or Abbas, Hussain’s half-brother, who went to fetch water but had his arms cut off by the enemy, then in his dying moments clenched the pail in his teeth as he staggered, mutilated, towards the camp.

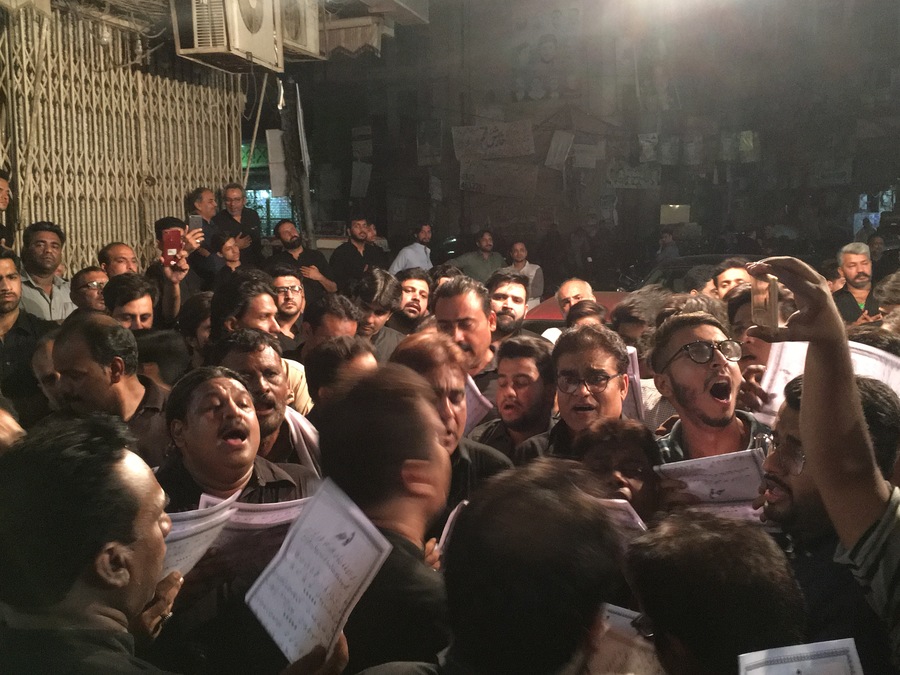

Group of “noha khawan” chanting noha in the streets of Lahore

Out in the street, the scene was even more emotional, as the ritual of matam had begun. Matam is a general term for physical grieving, which may including anything from chest-beating to self-flagellation. The groups of matamdari move around the Walled City of Lahore at night during the first ten days of Muharram, an alam (pendant) in front, a group of people chanting mourning songs called noha to a marching beat, and then a larger group of men beating their chests in synch with the noha.

An alam in the Walled City of Lahore

Matam in the Walled City

The noha and matam groups move around the city, inviting anyone and everyone to take part. There is usually one central group who maintain the rhythm, while others may join. Usually the main group of male matamdari have their shirts off, to try and make the practice as visceral as possible, while the noha khawan (chanters or reciters) remain fully clothed. The men who are not part of the main group usually stand on the fringes, adding to the atmosphere, and gently beating, or even simply tapping their chests in a mark of solidarity. Women usually stand to one side, or look over the group from balconies, although there are dedicated female matam functions which take place behind closed doors (and fully clothed, of course).

Anyone else on the street at the time, even if they are not involved, usually stops to watch the group pass – either out of respect, or simply to witness the spectacle.

A group of mourners watch on, silently tapping their chests the the beat of the noha

These guys were either responsible for the speaker pumping out nohas… or they were just watching on in awe.

Everyone, from the young to the old, gets involved in some way, although it’s also important to point out that this is voluntary – as someone told me; “we do this because we want to. It doesn’t really work if it’s not from the heart”.

As you can imagine, matam is hard work, and as the processions move around the city there are sabeel stands to serve up cold water to the sweaty mourners, other participants, and anyone else that it passing by. In Karbala, Hussain and his camp had been surrounded for days, and their water supply cut off – by the time the massacre took place, the group were dehydrated and desperate for even a sip of water. As such, the act of giving water to the mourners, or just about anyone, has symbolic and spiritual significance – an act of humanity, not simply hydration.

This child took over the sabeel stand for a while when his father went to refill the water tank.

Connected with the idea of sabeel is niyaz; food packages handed out to anyone who passes by. An act of charity, humanity, and donation. It might simply be a packet of biscuits, or it could be a plate of pulao (lightly spiced rice) or paratha-style sandwiches.

For those who perform matam and noha, it is often eaten after the procession ends, but it’s also given to anyone who approaches the niyaz stand. Niyaz has spiritual significance too – for many people, there’s something holy about taking in food which has been prepared for the sake of Hussain and his family.

Preparing niyaz on a side street

Walking through the Walled City during Muharram is uncovers other fascinating scenes too. The processions are always proceeded by the alam (pendant), and anyone is welcome to start their own procession (although anything except small, family-led processions requires a police permit as the road is closed). As such, shops selling alams, flags and other auspicious items stay open all night long.

The hand of the alam represents the “Panjtan Pak”, or the “five pure members” of the house of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ; the prophet himself, his daughter Fatima a.s, her husband Ali a.s, and their children Hassan a.s and Hussain a.s

Another feature of many processions is the zuljinah, a horse which represents that of Hussain. It is said that during the “battle” Hussain rode his heroic horse which didn’t flinch, and then the horse refused to give up on his master even after the enemy swung his sword for the fatal blow.

Zuljinah amid the melee on 10th Muharram

The zuljinah is elaborately decorated and then guided through the procession, evoking among the mourners strong emotions of loyalty amid the tragedy.

Preparing the zuljinah for his journey through the city

Symbols used in “dressing” the zuljinah include a white cloth splattered with red dye to represent Hussain’s blood; red dye applied to the horse’s lower legs to symbolise the river of blood that resulted form the massacre; a shield and sword, and a turban or crown on the zuljinah’s back to represent where Hussain would have sat. These horses are never ridden, always guided by a tether; the message is clear – no-one could ever take the place of Hussain.

As the days of Muharram wear on, particular processions are dedicated to the memory of particular martyrs at Karbala. On the evening of the sixth Muharram the procession features a cradle to represent that of little Ali Asghar. This, for me, was one of the most emotional parts of the ten days; the empty cradle is lovingly carried through the streets, as mourners rush forward to touch it, paying their respects to the six-month old who was killed in a state of serious dehydration.

Mourners, with a significantly larger proportion of mothers, look on as the cradle of Ali Asghar is carried through the city.

The procession for Ali Asghar begins in the mid-evening and concludes mid-morning. As it reaches an area known as Chuna Mandi, just after dawn, a group of noha chanters begin to sing a lullabye for the baby in his physical (but not spiritual) absence – it was easily one of the most heart-wrenching scenes I’ve ever encountered.

The sun rises as Ali Asghar’s cradle is taken through the Chuna Mandi area of Lahore’s Walled City

On the night of the seventh Muharram mehndi (henna paste) is handed out to the mourners. This relates to a story that, three nights before the massacre, a wedding took place in the tents at Karbala. The story goes that Hussain had promised his late brother, Hassan, to take care of his son and to organise his marriage. Knowing that they were days away from being slaughtered, Hussain organised the wedding to fulfil his promise. There are varying accounts of how (and even if) the wedding happened, but in the most heart-rending version Hussain’s sister Zainab applied henna to the hands of the couple to make the wedding as complete as possible. In the absence of water, and knowing what was to come, she used her own tears to mix the henna paste.

Mehndi (henna paste) being handed out on the seventh Muharram.

On other occasions, such as on the 9th Muharram night, a symbolic shrine is carried through the city to honour Ali Akbar, Hussain’s eldest son, who was also murdered at Karbala. The golden shrine attracts throngs of mourners who rush forward in a scrum to touch their hands, faces, heads or even to kiss the shrine.

Another shrine is made from plant matter, and through the first ten days of Muharram is fed water, sprouting grass by the evening of the ninth when it is carried into the city.

The evening of the ninth of Muharram is also the time that zanjeer markets are at their busiest. Zanjeer literally means ‘chain’ in Urdu, and in this case evokes the memory of the chains that were used to shackle the survivors of Karbala when they were taken prisoner. The zanjeer markets are not quite about chains, however – this is where the five bladed whips used for self-flagellation are made, sharpened and sold. The five blades take different shapes, ranging from small talwar (swords) which call to mind the swords used at Karbala, to larger, heavier implements shaped like cleavers. They are attached to a handle with individual chains, and as such are called zanjeer.

It was fascinating to watch the craft of the men who were making the zanjeers. Many are sold ready-made, but many are also tailored according to the user’s desire – sharper, blunter, heavier, lighter, bigger or smaller. Were the subject matter not so serious, it would be almost quaint.

The evening of the 9th Muharram is the most solemn of all – the night before the massacre, when everyone in the hopeless situation at Karbala was awaiting their fate. The most emotional part of the night is, undoubtedly, the early morning call to prayer on the 10th. Mourners stay awake for this moment – this year in Lahore it took place at about 4:15am. At Karbala, the call to prayer for the 10th Muharram was given by Ali Akbar, who knew that it would be the last call to prayer he would ever perform. Today, the call to prayer on 10th Muharram is known by many as azan-e-Ali Akbar, “Ali Akbar’s call to prayer”, which heralds the beginning of dawn on the fateful day of Ashura.

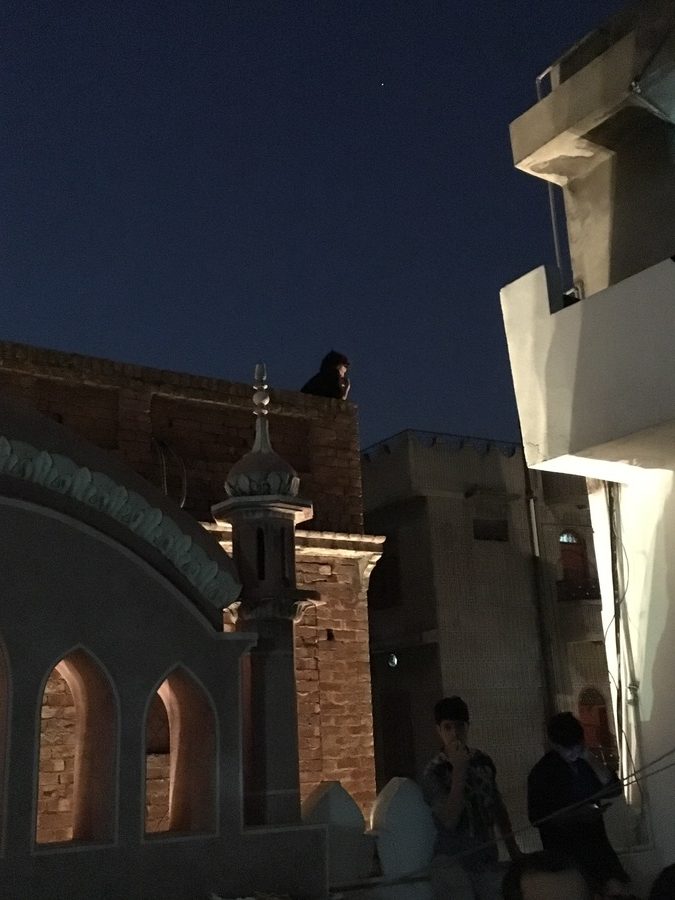

The Kashmiri Mosque in Lahore on the morning of 10th Muharram.

A woman watches on from her terrace as the emotional scenes unfold on the street below

As one of the most emotional moments of the day, the call to prayer is the moment when the greatest displays of sacrifice begin to occur on the streets. The crowd, numbering hundreds of thousands, have sat in the streets all night long in quiet remembrance of Hussain, but at the moment of the call to prayer men spring forward from the crowd and begin to flagellate themselves with their zanjeers. Some whip a few times to draw some blood and feel the pain of Hussain, while others slash their backs for minutes, allowing the blood to flow as a sacrifice for their imam.

Powder is thrown into the air as the call to prayer begins

Among the gathered crowd, the majority were not participating in flagellation. Instead, they were watching on, crying, screaming, some even beating their heads and faces in the deepest grief I’ve ever witnessed. Some were chanting “Ya Hussain”, while others were crying as they envisioned the massacre of Karbala in their minds; the amount of blood on show in Lahore on that day was nothing compared to what has been described from Karbala. Anyone close to the ritual gets sprayed with flecks of blood – there’s certainly enough of it dripping from the zanjeers as they are swung around.

So passionate were many of the men flagellating themselves that their companions would intervene to halt them when they felt that they had done enough damage. Generally the cuts aren’t too deep, and most zanjeer zani participants clean themselves up and continue with the day, however ambulances and first aiders are on hand for those who take things too far, or if a stray blade hits somewhere (or someone) it wasn’t supposed to.

A small handful of men practiced qama zani, a more extreme version of zanjeer zani in which a knife is taken to the scalp; usually these men would only make a few strokes before their friends or brothers intervened, rushing them to a first aid post to be examined.

A man practices qama zani during the azan-e-Ali Akbar

As the call to prayer winds down, the self-flagellation also slows and the crowd begin to disperse. Many of the mourners keep a kind of fast known as faqa, in solidarity with those who were present at Karbala – they break their fast in the mid afternoon, at the time when it is said that Hussain was killed. The mood immediately after the call to prayer was one of release, but also incredibly poignant, with a realisation that the day of Ashura was dawning.

A man, having performed qama zani, looks on as the crowd disperses after the call to prayer.

A crowd scrambles for niyaz on the day of Ashura; those who aren’t fasting usually get their breakfasts from places like this.

As the sun rose over the Walled City of Lahore, processions continued through the morning, triggering more spontaneous outbursts of emotion, grief, and acts of remembrance. The city’s main procession leaves from an area known as Mochi Gate, a centre for Lahore’s Shia community, and takes about twelve hours to reach a shrine known as Karbala Gamay Shah on the other side of the city. This procession almost has it all; pendants, flags, the zuljinah, noha chanters, matam groups and, as it passes around the city, more men break through the crowd to brandish their blades and flagellate their backs. The streets are lined with people in anticipation of the procession’s arrival; in its wake it leaves crowds emotional, distraught, crying, and splattered.

Noha khawan chant noha in the Walled City on 10th Muharram,

A group try to restrain a man, overcome with emotion, as he tries to strike his head out of sheer grief

Zanjeer zani being performed in the streets on the morning of Ashura

As mesmerising as the incredible displays of grief being played out on the street were, it was also equally fascinating to watch the crowd who came out to witness it. Local women residents poked their heads out of windows, not wanting to get involved in the male-dominated chaos of the street below, while children got a birds-eye view from the windows of mosques and other public buildings.

The day of Ashura continued to unfold across Lahore until the evening when all the processions reached their destinations when one final majlis is held; Sham-e-Ghareeban, the evening of the sullen/desolate. The Sham-e-Ghareeban majlis is an exercise in impassioned, deeply moving heartbreak – it remembers the evening when, after Hussain’s death, the survivors (mostly women and children) were looted from, shackled, taken prisoner and had their tents and few belongings set fire to. The lights are switched off at the Sham-e-Ghareeban majlis, and from the darkness all that can be heard other than the voice of the speaker is anguished, pained cries of misery.

The mourning of Muharram is not any ordinary event, it is an important juncture in the calendars of many, whether they mourn or not. It’s deeply affecting to experience such passion, unsettling to hear the stories of what occurred at Karbala, and astonishing to observe grief on such a wide and deep scale. On one of the earliest days of Muharram I saw one young boy walking into a majlis wearing a T-shirt that read “There is no other day like O’ Hussain”. I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Tattoo of faith; this young man, awaiting the procession’s arrival, bears the scars of previous sacrifices.

Level and wonderful 😍😍😍😍😍😍😍

Thanks Haroon 🙂

Wonderful reportage, really takes you there and stunning photos.

Thanks for reading 🙂

Looks like moving, powerful stuff!

It certainly was! Thanks for reading Andy 🙂

Interestng article Tim. Sounds really intense.

Thanks for reading, mum x

Very Detailed and Powerful

Thank you!

Very reflective article.I am amazed how well you are able to connect to the feelings of the mourners. Just to add hope you knew it already that along with the emotions there are some good scholars who recite majlis in a way that they lift the listeners intellectually as well.There are good scholars in west as well who lecture upon topics such as self improvement and purpose of life during majlis.

My own life have changed and became veey purposeful after listening such lectures/majalis.

Wonderful! Thank you for your kind words 🙂

Welcome to karachi

Thank you 🙂

As a Sunni and a student of history, Karbala has always fascinated me beyond anything else. The sacrifice of Husayn ibn Ali and his companions is one of the most sorrowful incidents in human history. As an orthodox Sunni, I was brought up loving the Ahl-ul-Bayt, and learning about the history of Karbala has given my love for them, a new life.

Tim, I did not know of you or about your work. I stumbled upon it accidentally and the name of your website intrigued me. I have thoroughly enjoyed reading this piece and your pictorial coverage of the occasion.

Much love and respect,

Umair

Hi Umair,

Thank you so much for your kind and thoughtful words! I’m glad you enjoyed the article 😀

Big respect 😀

Tim