Heer Ranjha: Pakistan’s Romeo and Juliet

One thing that I have come to realise as I’ve travelled around the world is the enduring popularity of tragic love stories. There is something about two people being so desperately in love with each other, yet unable to act upon their romance that strikes a chord with societies in almost every country I have spent a long amount of time in. Earlier this year I made a vlog about Japan’s Ohatsu Tenjin Shrine where two star-crossed lovers paid the ultimate price for their love. A few years ago I watched the lavish cinema production of Ram Leela, a similar story from India; Iran and the Arab world have Layla and Majnun, and everyone knows about Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Pakistan is no exception, although the story of Heer and Ranjha is so entwined with the fabric of local tradition it’s difficult to know where reality ends and the story begins. The story goes that the beautiful young woman Heer fell in love with Ranjha, but was forced by her father to marry someone else. Ranjha leaves, heartbroken, but after a spiritual awakening he returns to take the lady he truly loves. Heer’s parents relent and seemingly allow her to marry Ranjha, but on the morning of the marriage she is served a poisoned meal – punishment for her behaviour. Ranjha rushes to her aid but finds her in the final throes of death. Knowing the only way he will ever be with her is in the afterlife, he consumes the remainder of her spiked food.

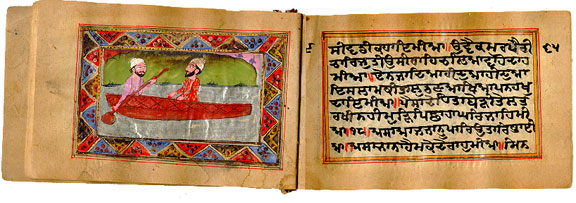

Ranjha being ferried across the Chenab River (Image: Unknown, Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Heer Ranjha is a Punjabi epic which transcends borders – movies based on the story have been made in both Pakistani and Indian Punjabs, and even non-Punjabi Indian films have referenced the tale. The folk story of Heer Ranjha was traditionally handed down from generation to generation, but the most famous version of the tragedy was written by Sufi poet Waris Shah in 1766. Here’s here the Pakistan connection comes in – Waris Shah lived and died in the part of Punjab which now lies in Pakistan.

But that’s not all – Heer and Ranjha are said to have been real people who actually lived and died in the city of Jhang in far western Punjab. Jhang has an unenviable reputation in Pakistan as being a real “wild west” town – the kind of place where anything goes, and tourists are cautioned against visiting. Years after moving to Pakistan, I finally got my chance to visit.

Downtown Jhang; Pakistan’s wild west

The trip to Jhang is just over three hours from Lahore. The bus was full of the usual suspects – restless children crying in their mother’s arms, a handful of cheeky male students on their way back from the provincial capital for the weekend, a poor young woman who suffered from motion sickness from the moment the bus pulled out of the station, stern-looking turbaned religious types who made eye-contact with no-one, and a man with a long, straggly beard sitting on the aisle seat, his veiled wife safely cocooned between him and the window. I fell asleep almost straight away, and was woken as the bus jolted into the outskirts of our destination.

Disembarking the bus, I was immediately accosted by about seven rickshaw drivers offering their services. Using my usual trick, I casually told them “nahi“, then walked off on my own. Once the commotion of the arriving bus had died down, I quietly approached a rickshaw driver on the side of the road, told him my destination and negotiated a price.

The graveyard near the Heer Ranjha Shrine

Western Punjab is a semi-desert landscape, and Jhang looked the part. The gentle but steady breeze swirled the dust across the road, even in the city centre. The rickshaw passed scores of locals at the roadside produce market, buying up fruit and vegetables, and scurrying from shelter to shelter, trying to avoid the heat of the sun’s mid-morning rays. Groups of women in black gowns held their chadors aloft to shield their faces from the harsh light. My rickshaw driver was a friendly but serious fellow; I got the feeling that he was probably quite hospitable, but life in the desert had taken its toll on him. I also wondered whether he might have been a bit confused, intimidated or even bewildered to meet a foreign traveller – tourists are not a common sight in Jhang, and on a subsequent trip to the Jhang area I was informed in one tiny village that I was “the first foreigner to come here”! Quite an honour (if it is indeed true), and a responsibility, too.

Very soon the rickshaw driver stopped, and asked me if I wanted him to hang around for the trip back. Surveying the desolate graveyard on the city limits, I figured it was a good idea. Alone, I walked through the rows of simple tombs which I assumed belonged to locals. It wasn’t long before I arrived at the shrine – a stout, square building topped with an open dome and four small minarets, its walls decorated in a strange checkerboard pattern. It was quiet, with very few people around, so I had the shrine almost to myself, save a group of men singing qawwali with an accordion outside.Their music took the edge of the atmosphere – instead of being uncannily quiet (like in the graveyard), the tomb was alive with love, dreams and melody. The strains of Dama Dam Mast Qalander, the transcendent Sufi chant from Sehwan Sharif, filled the air.

I entered the small building and was almost immediately faced with a single, dark brown tomb. I was surprised by how small the room was, and how the single tomb was literally all there was inside. The tomb’s headstone was decorated with garlands of flowers red, crimson and marooon. These colours were accentuated by the tomb’s walls, awash in rose, straw and indigo. The roof was a dome around the edges, but the top had been omitted from the design, meaning the centre of the room was open to the elements.

I knew I had to get my camera out, but I had noticed a sign which clearly said that photography was not allowed and at the entrance was seated an elderly attendant, his face lined and wrinkled, his balding scalp barely hidden by a roughly tied red turban. I decided to try my luck anyway, so I turned to the shrine’s attendant and pointed to my camera, to which he silently nodded his approval. I had only clicked a few photos when I heard a voice from just over my right shoulder;

“Heer AND Ranjha are in there…” said the voice in Urdu, gesturing towards the grave. I didn’t have to look back; I instinctively matched the gravelly voice to the attendant’s solemn face. I felt a gentle hand on my left shoulder, and he was now standing almost next to me. “…and,” he said, pointing at the open roof, “…when it rains in Jhang, it doesn’t fall in here.” I wasn’t sure what to say – I stared at the flawless blue sky, wondering how much to believe the attendant, and pondering how often it rains in Jhang anyway. I felt the hand leave my shoulder, and he silently made his way back to his position at the entrance. I continued to take in the shrine, and although it had only been about thirty seconds, by the time I turned around the attendant had dozed off. I left a small donation and left the shrine.

As I walked down the steps to collect my shoes, a small group of young men and women entered, chatting and giggling. As they approached the shrine their laughter died down, and they began to murmur prayers for the departed souls. This is where the Heer Ranjha story is so different from that of Romeo and Juliet; I can’t imagine Romeo and Juliet being prayed for in this way. It makes sense, somewhat – if Heer and Ranjha were indeed real people; the Sufi qawwali heightens the spiritual factor; the poet Waris Shah was himself a Sufi preacher, and in his poetic version of the story Ranjha wanders the Punjabi countryside chanting the name of God until he realises he and Heer are destined to be together. And in Jhang, whether you believe the story or not, Heer and Ranjha are finally at peace – together.

lovely. tragic, but together.

Thank you 🙂

Amazing story, and journey, Tim. Thanks for writing it. As an ex-pat Punjabi (from the Indian side), I am fascinated that you pursued the Heer-Ranjha story timeless as it is … Never visited Lahore either, but your stories create an imaginary world for folks like me … where you take us and we feel the joy too! Keep it up!

Thanks for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed it! It’s a beautiful, tragic story, and it is such a timeless epic <3

Love the description of the tomb and the visit to Jhang. Makes me want to go back to Pakistan!

You’re always welcome back! 😀

Thank you for sharing this post really great and wonderful article. You are talking about Heer, Ranjha and Romeo Juliet which are really well-written.

Thanks for reading!