I’ve never been particularly interested in pursuing mainstream hobbies; when I was in first grade, I told my parents that I wanted to play the cello, learn Polish and practise archery. Go figure. While I never did take up Bhutan’s national sport, my interest in unusual languages has not dwindled. In fact, I now know that “chelo” is not just a string instrument, but also the way to say “let’s go” in Urdu! Urdu is the language I started trying to teach myself in 2006. It’s a language of romance and steeped in poetry. It’s a language of philosophy, of culture, and of community.

Taj Mahal at sunrise

What is Urdu?

Urdu was developed relatively recently in Delhi and Lucknow, a large Muslim-dominated city in northern India. It came about after north Indians (speaking varieties of Hindi language) were ruled over by the Persian-speaking Mughal empire. Naturally, Hindi adopted several Persian words and grammatical structures, but the issue of alphabet remained. Hindi used the traditional Devanagari script, while Persian used an Arabic script. See the following example;

“The table is in the room”

Devanagari-script Hindi: “mez kamre mein hai“: मेज कमरे में है

Arabic-script Hindi: “mez kamre mein hai“: میز کمرے میں ہے

This awkward difference continued for hundreds of years under the Mughal empire, but came to a head in the 1800s when Britain had to decide upon an official language for its new colony, India. Persianised Hindi, by then referred to as ‘Hindustani‘, was named as the national language, but was to be written in the Arabic-Persian script. This naturally triggered a backlash from locals who wrote with Devanagari, however Indian Muslims mounted a counter-claim that the Arabic script mightn’t have been native, but was culturally more appropriate (given the Arab-Muslim connection).

Jama Masjid and the streets of Delhi, India, where Urdu was developed

Hindi, or ‘Hindustani’, was split in two; between Hindus who would write the language using the Devanagari alphabet, and Muslims, who would write with the Arabic alphabet. To speak, there would be very little difference. The word ‘Urdu’ was given to the Arabic-script Hindi as far back as 1780; ‘Urdu’ is a Turkish word meaning ‘army’; Urdu is the language which was developed by the Persian army of Mughal India. In fact, the English word ‘horde’ is a relative of the word ‘Urdu’.

Although it was developed in areas of India, Urdu made a logical choice for a national language when Muslim Pakistan was created in 1947. (Hindi remained one of India’s national languages). Since then, efforts have been made by Pakistani authorities to distance Urdu from Hindi by replacing ‘Indian’ sounding words with Persian equivalents – in effect, to further ‘Persianise’ and ‘Arabise’ the language. Likewise, India has gone (and continues to go) to great lengths to ‘purify’ Hindi from Muslim influences. Both schemes have met with mixed success.

Urdu is associated with poetry and literature, and of the prestige of the Mughal dynasty which gave the subcontinent such icons as the Taj Mahal, and Lahore’s Badshahi Mosque. It is a language of love, of beauty and emotion; the words as vivid and colourful as the society it aims to describe. It is often employed as the language of Bollywood films due to its cultured, romantic association.

Sunset over Badshahi Mosque, Lahore

Learning Urdu

So it was that in 2006, with a little background in Persian and Arabic, that I decided to take on Urdu. My initial progress was slow, and despite ordering a pricey book and CD kit in 2010, my skills didn’t really advance past the elementary stage. Living in Chennai didn’t help either – most people I came into contact with either didn’t or wouldn’t speak Hindi or Urdu, just Tamil.

In 2014, eight years after starting, I decided to get serious about learning the language of the country in which I was to emigrate to: enter Mr Naveed Rehman. Mr Rehman is a Lahore-based Urdu teacher who has a background in accounting. It has been several years since he swapped the comforts of the office to teach the language he loves, but his passion for his native tongue shows. Urdu is not an easy language to learn for English-speakers, but Naveed makes it simple with a rapid learning process which focuses on vocabulary and conversation. The alphabet and script can come later; his students are encouraged to begin with Anglicised transcriptions of Urdu words.

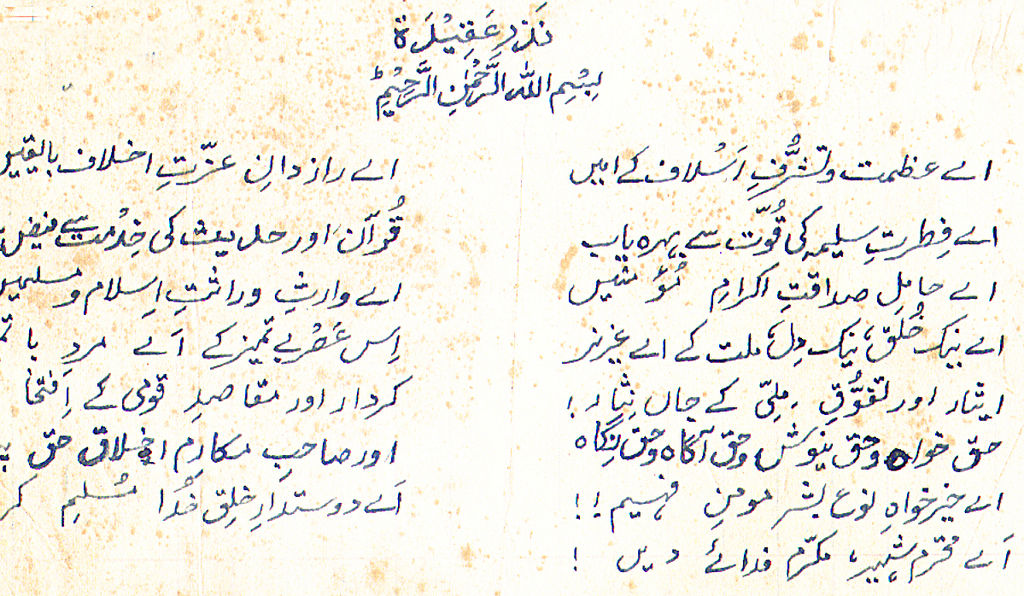

Poetry written in Urdu (Image: Atif Sati, Wikimedia Commons)

He is also very flexible, offering classes at home, at several colleges and online via Skype. I can honestly say that I have learnt much more from him in eight months than I did in the eight years prior. I am already into advanced grammar, and can’t wait for the day when I begin to study the philosophical concepts and poetry that make Urdu the sweetest tongue of the subcontinent.

Naveed Rehman

If you would like to learn Urdu, I highly recommend you contact Mr Naveed Rehman either by email (rehmannaveed72@yahoo.com) or phone (+92) 03004200729 to arrange effective lessons at an excellent price!

“Tu shahin hai parwaaz kaam tera, tere saamne aasman aur bhi hai.”

“An eagle you are, born to soar, skies galore for you to scale”

– Allama Muhammad Iqbal, Pakistan’s national poet and master of Urdu.

Haha, does he teach Bosnian, too?! (That’s the language I’m currently struggling with but determined to learn…) This was an inspirational post for me though, language learning is definitely not simple but when you realize you’re making progress it’s very exciting!!

I wish I could help you with the Bosnian!! Yes, it’s so motivating when you see yourself making progress. Good luck with your study!! Thanks for reading 🙂

Wow Tim,

You surprise me every time! Urdu is my second language, if you need to practice speaking Urdu you can add me on Skype 🙂

Annie ox

Thanks Annie! Very kind of you! Thanks for reading 🙂

(Parindon ki dunya ka darveash hn main

k shahin banataa ni ashianaa ) 🙂

Amazing 🙂 Sir you Know Better history of Urdu than me. IT shows how you love Our language 🙂 🙂

Bahut shukriya Haroon 🙂 I’m glad you enjoyed it!! 🙂