It’s not often that you feel as if you are truly crossing a civilisational frontier. It occurs, predictably, on flights operating between contrasting worlds, such as from New York, USA to Riyadh, the Saudi Arabian capital. It also occurs at major watersheds, such as the Karakoram Highway which crosses from Pakistan into China, switching the side of the road with it. And then occasionally it occurs within a nation, for example in Sydney when one (anyone?) travels through the Cross City Tunnel, descending from the salubrious Eastern suburbs and emerging enroute to the decreasingly grungy inner west. It was with such a thought in mind that I embarked on a road through China’s Tibetan areas, in the western section of Sichuan province. I approached from Kathmandu, as part of a wider trip. On the flight from the Nepalese capital to Kunming, in southern China, the plane passed Mount Everest’s blunt peak scraping the clouds away, just a taste of the vast mountain range that lay below the endless cumulus carpet.

The ascent

Kunming is a large city in China’s south – it’s an important city for business, being so close to the borders with Vietnam and Myanmar (Burma). It is the capital of China’s Yunnan province. The city is also a fairly important gateway to China, with a brand new, cavernous, seriously spectacular airport receiving flights from India, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. I spent a few hours in the terminal, sorting out my connecting China Eastern Airlines flight at no extra charge, then eventually checked in to the domestic leg to Lijiang (see map; http://www.yunnan-roads.com/yunnan-roads/yunnan-map.htm ; Kunming is in the centre, Lijiang northwest from there). I arrived late into Lijiang, at about 1am. Lijiang is a medium-sized tourist city designed to recapture the old style of Chinese towns, replete with turreted roofs and tea houses. Lijiang is home to the Naxi people, a small ethnic group with their own language and traditions. Newly middle class Han Chinese flock to Lijiang in their thousands to see a piece of the “Old China” and learn about the Naxi tribes. Honestly, it’s all a bit contrived; Lijiang’s ‘old town’ was actually built specifically for tourists about fifteen years ago, so it’s not really old at all. However if you can put that out of your mind and just take it at face value, you can still spend an enjoyable day sipping the local tea, poking around temples and wandering the photogenic cobblestone markets. I stopped in for lunch at a small restaurant beside a canal where I ordered a vegetable noodle dish. In this part of China, learning to eat with chopsticks is your only hope of getting a meal. Likewise learning a few words in Mandarin – in some small towns, even the word “Hello” is met with blank stares. While in Lijiang I stayed at the very friendly, family-run Panba Guesthouse. I ate dinner with the Panba family who had cooked up a delicious vegetarian storm. (Non-vegetarian option is standard, but contains pork).

The next morning it was time to leave; Lijiang was always just a transit stop for me, enroute to some serious mountain scenery. Fellow backpackers I had met in Lijiang were headed the same way, so we caught the same bus together out of town and up into the Himalayas. During the four hour ride we were kept entertained by an overconcerned lady behind me, who had packed a small oxygen cylinder to use in case of altitude sickness. She began gassing herself the moment the bus pulled out of Lijiang’s bus station. As we approached our destination some of the non-local passengers began squealing with delight when she spotted some piglets running around a pen beside the road. It was on that trip that I remembered the Chinese aversion to fizzy drinks – the bottle of Fanta which I had packed had more of a sherbet-like fizz than the sparkling western version, and it went flat more quickly. Foreign companies adjust their products for their customers, and in China, that means less carbonation. Fanta also comes in green apple and grape versions, reflecting the Chinese palate. Once upon a time they had a limited edition Beetroot Flavour Fanta – it may sound weird to us, but then a drink made from the African cola nut sounded pretty weird to them back in the 1970s too.

My next stop, Shangri-La, was where I began to enter the Tibetan areas of China. It’s about 300 Kms from the official Tibetan border and the town is roughly half Tibetan and half Han Chinese. Previously named Zhongdian, it took a leaf out of Lijiang’s book and it renamed itself a few years ago as part of a tourism campaign, then started building an ‘old town’ in the style of old Tibetan villages. (On the map here, it is listed as ‘Shangri-La’ in the top left corner; (see map; http://www.yunnan-roads.com/yunnan-roads/yunnan-map.htm). At 3200m, Zhongdian is also very high, the air thin, and the nights cold; Helloooooo electric blankets! In fact I saw one man at my hostel quite sick from the altitude – the kind hostel manager and her husband were quite used to dealing with travellers who struggled to acclimatise. Again, the ‘old town’ in Shangri-La is very new (still under construction, actually), but I was glad to start witnessing the Tibetan culture, which is rather noticeable there. Slowly, like the thick oxygenated air in the humid valleys below, the Han Chinese culture was beginning to fade away. The next day I boarded a bus bough for Deqin, in the far north-east of Yunnan and enroute to Tibet proper (see map). The eight-hour bus ride was along a road which is currently being rebuilt; as a result of the heavy machinery, much of the bitumen was missing, and detours were in place, and occasionally the bus drove perilously close to the edge of sheer cliffs. Passengers would exchange worried glances everytime our minibus had to go “off-road” in the name of a detour. On the ride up, we passed a mountain of 5000 metres; the highest I have ever been. We also saw what the new road to Deqin will look like; huge pillars supporting a highway which will fly across the rugged valleys.

On top of the world…

Deqin (pronounced “der-ching”) is a fairly ugly service town occupying a valley 3550m above sea level. 15 minutes drive from Deqin, however, is the temple of Feilaisi, and its associated village, where I stayed. Chinese hotels do not usually offer a single rate, so it made sense for a fellow traveller and I to share a twin room in a nice hotel rather than shell out the same amount each for separate rooms in a crap hotel – so we did. My travelling buddy also spoke fluent Mandarin, so was able to negotiate a great price for us – I had chosen my buddy well! Most people come to Deqin area for the views; from our hotel room, we had a view across the Buddhist stupas to the Meili Snow Mountain, a soaring Himalayan peak of 6700m which, although the climate is tropical, is always covered in snow because of its height. The afternoon haze obscured some of the view, but everyone who comes to Deqin knows to wake up early to catch the first light on the towering mountain. My friend and I were up at 6am, breathing in the freezing air, when dawn broke. The sight was absolutely magnificent; the clouds from the day before had cleared to allow us a spectacular view of the dramatic mountain. As morning mist began to fill the valley below, the mountain seemed to float above the clouds. And as the dawn became day, the brilliant pure white of the mountain’s snow seemed to match the perfect white of the Tibetan stupas in front of us. The stupas’ golden crowns almost blinded us as they caught the sunlight, and Tibetan Buddhists circled them chanting their prayers and burning incense. Unforgettable. The rest of the day was spent doing nothing; apart from sunrise, there’s not a lot to do in Deqin once the day’s fog rolls in. Some tourists headed off to pay $15 to see a glacier on the side of the auspicious mountain; we skipped that and photographed it from afar. Instead we headed into town to buy our bus tickets back to Shangri-La the next day – we also took the opportunity to wander the markets in Deqin, full of all sorts of produce. The following day, after a slightly less hair-raising drive, we had one last dinner together at the stylish Compass Cafe in Shangri-La.

Parting company, I then set out towards the most Tibetan areas of my whole trip. From Shangri-La, I took a bus north on a lonely road which isn’t marked on the previous map. After about nine hours of winding switchback roads, fields of sunflowers, and dense, misty forests, the bus pulled into the blah town of Xiangcheng (see map; http://www.tibetmap.net/Maps/A-Sc1.jpg ; Xiangcheng is in the bottom left hand corner. Note the road heading north from the direction of Shangri-La). Xiangcheng is a service town for buses heading along the mountainous route from Yunnan province (on the previous map) and Sichuan province (on this map). The following morning it was into a minibus for the final haul up to Litang (on the map, just north of Xiangcheng). After three days back to back of BO competing with stale cigarette smoke on buses, Litang was a place to rest my head. I was driven to Litang by a local guy who seemed to have anger management issues, and after arriving safely checked into the basic but friendly Peace Guesthouse. Litang is one of the most Tibetan of towns outside of Tibet itself; it’s 85% Tibetan, and Tibetan is the local language; the main street is dotted with businesses advertising with the distinctive jagged script. Although isolated, it was full of foreigners like myself who had come to experience the Tibetan culture after the latest round of restrictions in Tibet proper. Litang is extremely high, at 4000 metres, and therefore has very little oxygen. In 2008 American singers Chris Brown and Jordin Sparks famously pondered how they were supposed to breathe with no air, the answer to which is Diamox. This wonder-drug can ward off altitude sickness in most people, and I can honestly say that while I occasionally felt out of breath, I never experienced headaches or dizziness the way other travellers did.

“Tibet Minor”

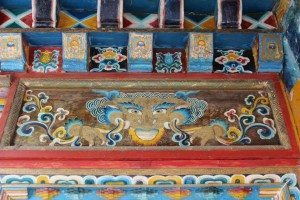

I spent nearly two full days in Litang, visiting the stupas and temples around town, and on Wednesday visiting Litang’s impressive monastery. The monastery was built by the third Dalai Lama in 1580, and its three large prayer halls still stand today. It was drizzling as I approached; being so high, Litang’s weather is very fickle and often wet. I climbed to the back to the monastery, on a hill overlooking the town, where the monks’ quarters were situated. There I met a few young monks who smiled, but spoke little English. Meanwhile, the weather was changing again, and a band of cloud had descended over the hills surrounding Litang. They spectacularly hung around the mountain tops like coits. Damp prayer flags fluttered in the breeze which blew across the grassy plains in the valley floor. It felt as if I was on top of the world, and that much closer to heaven. It also became clear that the rain was about to get much heavier, so I fled back to town to the shelter of a Tibetan restaurant. Tibetan food is survival food – temperatures often struggle past 10 degrees Celsius in the middle of summer, and the winters are unimaginably bleak. Yak meat stew and salty butter tea might not be on the menus in your hometown, but they are ubiquitous in Tibet. For those unfamiliar with yak meat (and I’m guessing that’s most of you), it tastes like slow cooked beef, and is similarly tender and slightly stringy. On Wednesday I worked up the courage to try a Tibetan favourite- butter tea with tsampa. Black tea is brewed as per normal, but then a dash of butter (made from yak’s milk) is stirred in. Salt, not sugar, is added to taste. The result is a warming, yellowish brew which isn’t as bad as it sounds. The spoonful of butter is added in place of milk, so it’s not thick or greasy – more soothing. Butter tea is traditionally served with tsampa, a warm, stodgy, crumbly cereal made from roasted barley. It vaguely resembles clumps of brown sugar, or too-dry bread dough. It’s savoury; almost flavourless, except for a bit of salt and sugar added. Tibetans often pour some of their butter tea into the bowl to make a porridge out of it. Later still I retired back to the guesthouse, where the owners invited me to share their yak meat stew for dinner. Having already eaten, I reluctantly said yes to be polite, but the dish was delicious. The mother had already finished her meal and was sitting on a couch across the room from me, watching me fiddle with the meat with my chopsticks. Meanwhile her teenage son slurped up the broth across the table from me and kept piling more food on to my plate from the centre dish.

On Thursday I headed out of Litang, and back towards earth. Overnight it had rained in the valley and snowed on the surrounding mountains. And yes, it was freezing. Some other travellers had gone off to watch a sky burial, a grisly Tibetan funeral tradition where the deceased are placed on a plinth atop a hill, and have their bodies pecked away by hungry birds which lie in wait. It’s not for the squeamish, but it forms a vital part in the circle of traditional Tibetan life where one must leave little trace after death – the body returns to nature, as naturally as it came. I was out of time, however, and spent the morning driving just above the snow line, skimming just below the clouds towards Kangding, the largest town in the Tibetan areas I visited (see map, just to the right of Litang). The road to Kangding is the worst road in the world, and twice we had to get out of the minibus to allow it to pass a muddy patch without getting bogged down. We saw several other heavy vehicles that hadn’t been as prudent, and they didn’t look like they were going anywhere quickly. Again, the valley was criss crossed by concrete pylons, signalling a better future for the Sichuan – Tibet Highway (although “highway” is probably too generous a term for the road in its current state. China knows how to build roads – it’s just a shame they’re still building so many of them.) Our minibus was driven by a smiling young local guy wearing a drizabone and an akubra hat. He afforded his minivan the kind of love and respect Tibetans might have for horses on the high plains, which was a refreshing change from all my other drivers. We finally pulled into Kangding, a modern gateway city to the Tibetan areas. Slowly, just like the snow on top of the mountains in Litang, Tibetan Sichuan was melting away into the hustle-bustle of Han China.

When to go

Go in July, August or September – they are the warmest months, and although most of China will be stifling hot, the mountains will be comfortable. Do not visit in March, when the region often closes to outsiders due to cultural festivals (see below). Suggested duration for this itinerary is 10 days minimum, 2 weeks to do it properly.

Difficulty

Culture shock: 8/10

Language: 9/10

Food: 8/10 (often you don’t know what you’re eating – just point at a picture on a menu!)

Comfort zone: 9/10

Physical demand: 8/10

Advice and warnings

Being so rich in Tibetan culture, western Sichuan is considered a politically sensitive area by the Chinese government. It is often closed to foreigners with little or no warning – a directive is sent to Shangri-la and Kangding bus stations not to sell bus tickets to foreign passport holders. Checkpoints on the road mean you can’t drive in either – and to “sneak in” would risk serious legal consequences. It is not unheard of for Western Sichuan to be “indefinitely closed” one day, then open the next – it really comes down to luck. You can only buy bus tickets one day ahead in any case, so you could easily get stuck at a bus station with no choice but to backtrack – have a good plan B ready to go!!

Some travellers have reported being inside western Sichuan at the time a closure was announced. In such cases they were kindly (but in no uncertain terms) advised by local police to leave as soon as possible.

It is not possible to travel to the state of Tibet from western Sichuan at the present time. Shangri-la and Deqin have not closed to foreigners in recent times.

There is little danger in visiting these areas, however if you see a protest or demonstration you should leave the area immediately. Do not photograph or enquire about politically sensitive subjects – you may get in trouble, but you could unwittingly also land someone else (a local) in much, much hotter water.

Altitude sickness is a danger in western Sichuan – speak to your doctor about remedies for this potentially fatal condition.

Internet access is restricted in western Sichuan – don’t count on being able to access emails until you get back to a major city.

Check Smart Traveller or the British Foreign Office for more comprehensive warnings.

Visas

Everyone needs a visa to enter the People’s Republic of China. Applications can cost up to US$100, and take several weeks to process. Contact your nearest Chinese diplomatic mission for details (Melbourne, Islamabad, Sydney, Delhi)

Getting there and around

From Melbourne and Sydney, China Eastern Airlines flies to Lijiang via Shanghai and Kunming.

Melbourne (from $1501 return)

Sydney (from $1328 return)

From Lahore and Chennai, you can fly Thai Airways International to Kunming via Bangkok

Lahore (from PKR 87000 return)

Chennai (from INR 35227 return)

Bus tickets generally cost between Y50 – Y100 per sector on this itinerary. Tickets must be bought at the bus station no earlier than the day before travel.

Accommodation

Lijiang: Panba Guesthouse

Shangri-La: Tavern 47 (bookable through Hostelworld).

Feilaisi Town: Lots of hotels dot the main street. We stayed at a small hotel with no English name on the hill behind the main street. Turn left out of the bus station and walk about 100m down the hill. On your right is an uphill street. Follow this around 50m to the first bend, then take the steps up to the upper road. The hotel is here. Very little English is spoken – and bargain hard!

Xiangcheng: Tibetan homestay – take the steps up into the garden at the back of the bus station. Keep walking up another set of steps, and the homestay is the 2 storey house there. The host will probably approach you when you disembark the bus anyway.

Litang: Peace Guesthouse – from the bus station, there is a fork in the road to your right. Take the left fork (the one that climbs the hill). About 50m up the hill on the left is the hostel.

Kangding: Gongga International Youth Hostel – I wouldn’t recommend this place, however it’s ok as a last resort. The staff and clientele were noisy and the rooms not particularly clean, however it was cheap. Ask around at the bus station.

Onwards

From Kangding, you can take a 6 hour bus ride along amazing freeways to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. From there, you can either fly out, or head back to Kunming, completing the loop.

Check out pictures from this breathtaking journey at UrbanGallery.

0 Comments