Lunch in a yurt at Lake Song-Kol

Lake Song–Kol is nestled high in the mountains in the foothills of the Kyrgyz Tian Shan, fed by the glaciers that scrape down their jagged peaks. At an elevation of 3000 metres, it’s frozen for much of the year, and when the ice melts it becomes a haven for nomads from the lower pastures and trekkers from abroad. In August the jailoo (moors) around Lake Song-Kol are filled with yurts and their residents herding sheep, yaks, donkeys and horses around.

Lake Song–Kol is nestled high in the mountains in the foothills of the Kyrgyz Tian Shan, fed by the glaciers that scrape down their jagged peaks. At an elevation of 3000 metres, it’s frozen for much of the year, and when the ice melts it becomes a haven for nomads from the lower pastures and trekkers from abroad. In August the jailoo (moors) around Lake Song-Kol are filled with yurts and their residents herding sheep, yaks, donkeys and horses around.

29 kilometres long, Lake Song-Kol is the second largest lake in Kyrgyzstan after the sea-like Issyk-Kul.

The two-hour drive on mostly unsealed road was bumpy and wet, rounding rugged, green, knots of hills as we drove up into the clouds. The road from Kochkor to Lake Song-Kol passes the 4000 metre mark, and I was warned about altitude sickness. Although I didn’t experience any serious trouble, for the first hour at the lake I couldn’t even look at the food which the locals offered me.

At the lake I spent a few hours strolling, taking pictures and enjoying something I had not heard for a long time; silence. The water was almost calm, gently lapping at the stones which marked the shoreline. It was cold, misty (actually in the clouds) and mysterious.

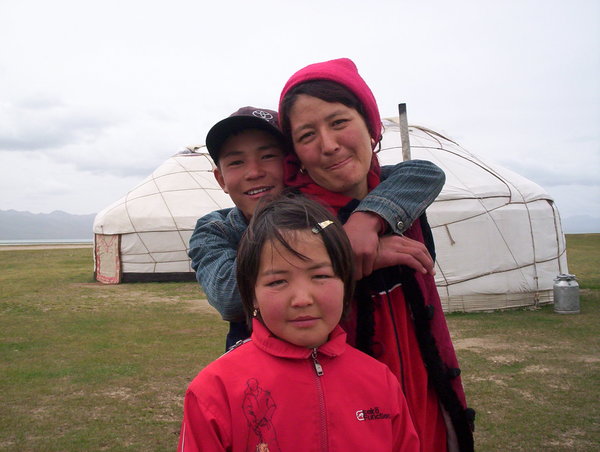

At midday I was met by Urmat, the friendly coordinator of Shepherd’s Life in Kochkor. He was a wealth of knowledge and had arranged for me to have lunch in a yurt with a local family near the lake.

I saw the meal made from start to finish; my hosts were in the process of turning a whole sheep into chopped lamb when I wandered behind the tent. I assume they were used to squeamish westerners who think meat comes from a supermarket fridge, because they tried to turn me away, but I told them it didn’t bother me. Once it was all in pieces I watched as the mother of the family turned those fresh morsels into a hot, hearty stew to be had with freshly baked bread. I also tried kumys, the local drink, which is actually tangy fermented mare’s milk (brave, I know!).

We had barely finished lunch and it was time to move – “the weather is closing in”, I was told, and we had a long and potentially slippery drive back to Kochkor. I was tempted to stay the night in the yurt – I had been extended an invitation, and the only thing warmer than the carpets and cushions inside the yurt was the hospitality.

However it was time for me to leave, and as a parting gift my hosts gave me a small carpet they had made, and a few pieces of kurut, dried yogurt balls which Kyrgyz people traditionally eat as snacks, especially when travelling.

On the way back I got speaking with one of my fellow passengers, a trader who was heading back to Kochkor after a day working at the lake. Translating through my driver, he described life in Kyrgyzstan and how things had changed since the end of the Soviet Union. “They used to hear helicopters at night and panic” he said, referring to his elder relatives. “Sometimes people would get picked up in the middle of the night, and they wouldn’t come back. They’d just disappear. They always hoped that the helicopters wouldn’t land near their house.”

Evidently life had changed in the cities and towns of Kyrgyzstan since the fall of communism. But my mind was still stuck back at the lake, where I felt that life and the time-honoured hospitality in that yurt had hardly changed in centuries.

i still am yet to stay in a yurt. I really want to. I want to stay in one so bad it yurts!

Oh I see what you did there, you punny man!