In the first of the Building Sydney series for 2016, I deliver an impartial analysis of the major infrastructure projects underway in the cities we call home. Today, we begin with WestConnex in Sydney, a 33 kilometre, $15 billion network of motorways in Sydney’s inner west and southwest, due for completion in stages between 2019 and 2023.

Sydney’s WestConnex: The Grand Plan

Ever since its announcement in late 2012, Sydney’s WestConnex motorway has been controversial. As visionary as it is a throwback, WestConnex is in fact the latest name (and probably the one that will stick) given to a network of motorways that have been under consideration to varying degrees since the 1960s.

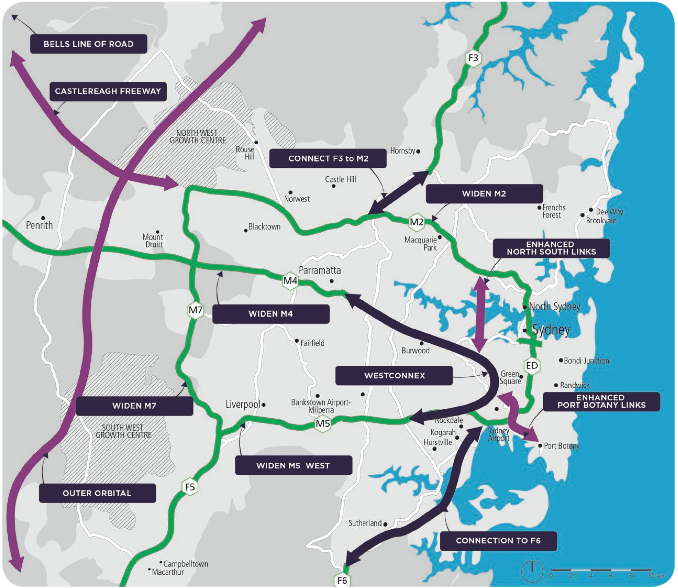

Sydney’s long term road transport plan (Image: Sydney’s Long Term Transport Master Plan, NSW Government, December 2012)

WestConnex is mapped out in three stages, but is actually part of a much grander plan for Sydney’s road infrastructure for the future. Dialogue surrounding WestConnex has so far been dominated by anti-road, pro-public transport sentiment, or pro-road and anti-public transport support. What doesn’t seem to have gained much currency is the idea of a dual solution, requiring huge investment, but potentially preparing Sydney with both public transport and efficient roads for a great future.

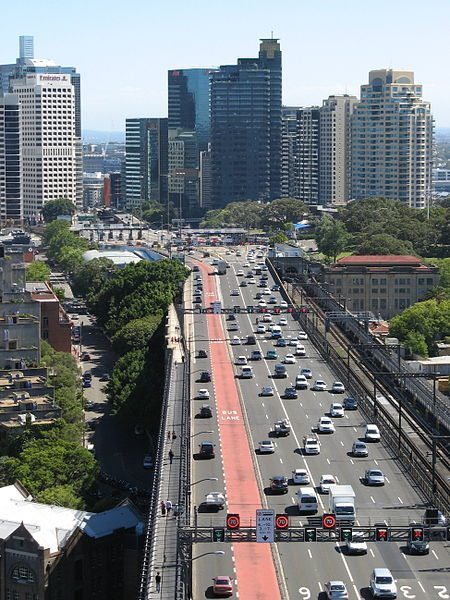

Parramatta Road near Burwood (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The necessity of a road linkage

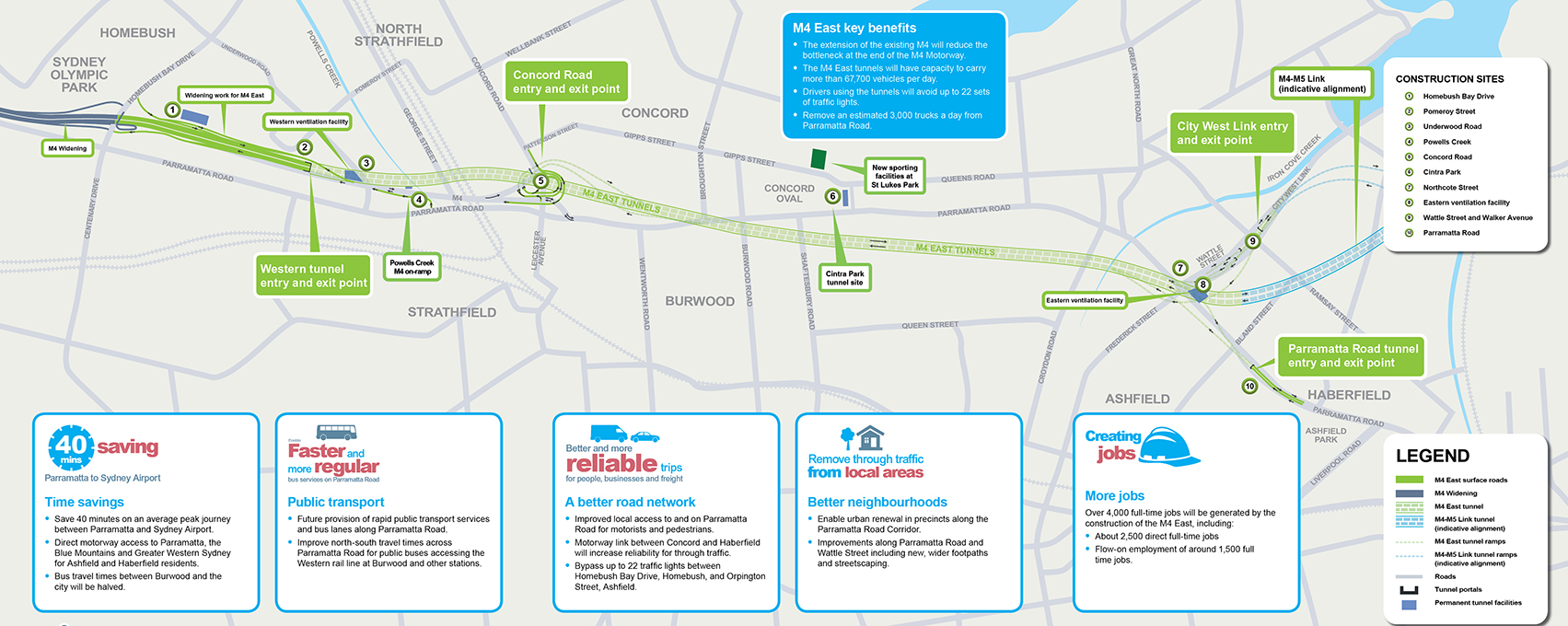

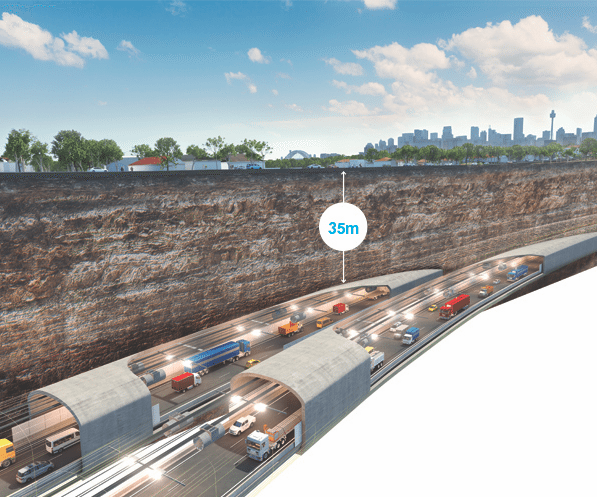

In the first stage of the WestConnex plan the existing M4 will feed directly into twin tunnels near Homebush. The tunnels will be 5.5 kilometres long, and known as the M4 East (as they are, effectively, an eastern extension of the M4 which currently terminates at Strathfield). Apart from the existing interchange at Concord Road, there will be no on-ramps or off-ramps between there and the end of it, at City West Link near Ashfield. City West Link is an arterial-road standard road, easily upgraded to motorway standard, which links Ashfield to the Western Distributor near the CBD, and then onwards over the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

M4 East Map (Image: WestConnex)

Environmental concerns aside, there is reason to believe that WestConnex will not solve the problem of traffic congestion on east-west roads from Sydney’s CBD in the long term. As with all roads, they are often filled to capacity within years, if not a couple of decades of their construction; as a result, major increases to public transit capacity must be considered alongside the road project, which is due to break ground in the middle of this year.

Sydney Train at Strathfield Station (Image: EurovisionNim, Wikimedia Commons)

Clearly, a large proportion of commuters travelling on the east-west axis have journeys that originate in the vicinity of Parramatta, which is often touted as the CBD of a future Western Sydney metropolitan area. More commuters still live in regions beyond Parramatta, which would ostensibly become satellite suburbs and towns of the Western Sydney metropolis (places like Penrith, Rouse Hill, Liverpool and Campbelltown). It would therefore make sense for Parramatta, apparent future employment hub of Western Sydney, to also become something of a transport hub, with light rail and bus options radiating out from the centre; indeed, plans for this are already underway.

Parramatta CBD (Image: Maksym Kozlenko, Wikimedia Commons)

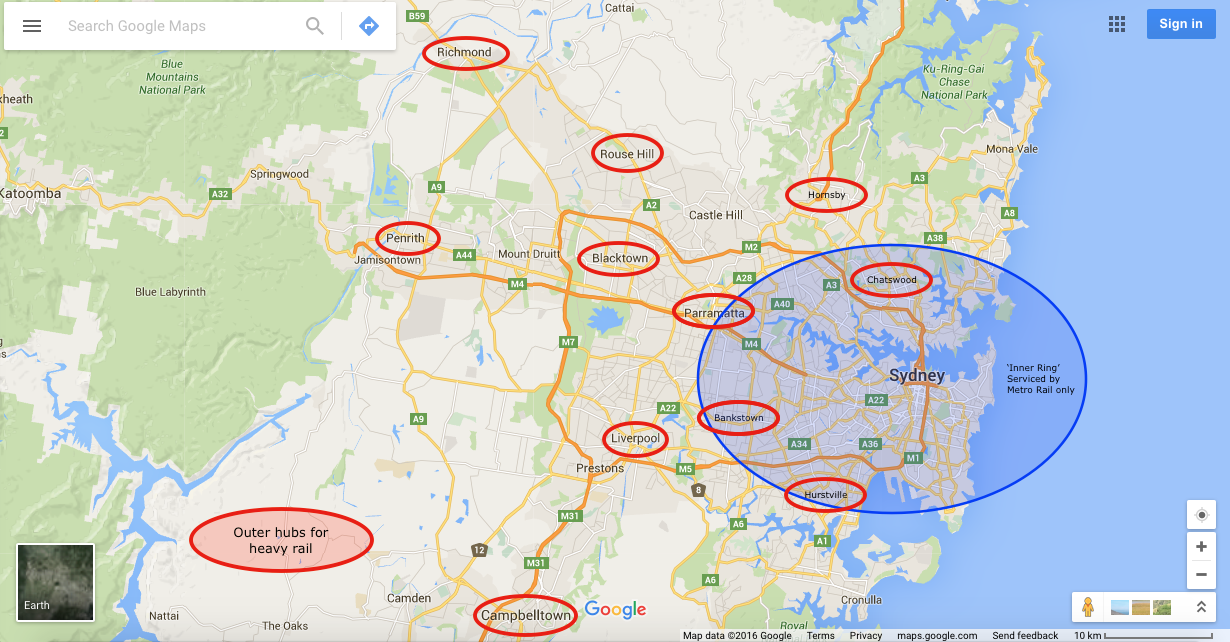

Heavy rail for the suburbs, metro rail for the ‘inner ring’

Presumably what will be required, then, is high speed, high capacity and high frequency linkages between Sydney’s old CBD and the new one at Parramatta. The existing rail network is able to do this, however currently serves the inner west as well as Parramatta and beyond. What could be done, however, is to utilise Sydney’s forthcoming rolling stock of metro trains on inner west lines, reserving the higher capacity existing trains to serve the outer suburbs. This, in effect, would be an extension of the current plan to replace the Bankstown Line trains with a metro-style fleet. The effect could be enhanced with further light rail options above ground in the inner west and east.

(Map: Google Maps)

What this would mean is a shift in thinking from heavy rail being the prime mover of Sydneysiders, to being a long-distance option between major points like Parramatta, Blacktown and Penrith or Bankstown, Liverpool and Campbelltown. Intermediate stops (like Seven Hills, Toongabbie, Mount Druitt or Werrington) would receive services, but the “inner ring” (i.e. – Central to Bankstown, or Central to Parramatta) would be served exclusively by frequent, high capacity metro style trains. This is an emulation of the European, and increasingly the Asian model of infrastructure development, and would buy years of additional value on the soon to be constructed M4 East.

Dubai’s new metro trains. Limited seating means high capacity (standing passengers take up less space than seated ones), ideal for fast, short inner city trips (Image: Robert Schediwy, Wikimedia Commons)

It’s worth remembering that the second stage of WestConnex is the duplication of the two M5 East tunnels, opened in 2002, and already filling up with cars, trucks and sundry. As if to acknowledge the deficiencies in the 2002 development, WestConnex Stage 2 has even been given the moniker “The New M5”. The need for a second pair of tunnels (that’s right, four in total) was announced in 2012 with the initial WestConnex proposal; just ten years after the original road opened, and that was before major development of the “South West Growth Corridor” got underway. At that same rate of growth, without being supplemented by a serious investment in public transport, the M4 East could require expensive duplication by 2029.

Overall, an integrated solution of public transport and roads is the kind of grand plan that Sydney often wishes had been implemented 50 to 100 years ago (Cahill Expressway anyone? Town Hall station crowded enough?). It would also dovetail with plans for Western Sydney’s development in conjunction with a new airport, as well as relieve pressure on the next stages of WestConnex, still under investigation.

Traffic on the Sydney Harbour Bridge (Image: Mitch Ames, Wikimedia Commons)

The Grand Plan

Stages 2 and 3 of WestConnex are already in the planning stage. Stage 3 envisions an extension of Stage 2 beyond Kingsford Smith Airport and up into the inner city, eventually joining the end of the M4 East. This would be designed to relieve pressure on inner city roads, particularly on the north-south axis between Kingsford Smith Airport and the inner west. It would also, indirectly, relieve pressure on the Eastern Distributor through Moore Park, by providing an alternative route by which to get to the city and beyond.

In the much longer term, the north-south link will be accentuated and extended in the form of the F6 extension (from Waterfall to the airport) and the Western Harbour Tunnel, a second harbour road tunnel to complement the Sydney Harbour Tunnel.

(Image: WestConnex)

While the Western Harbour Tunnel and F6 Extension are planned in the longer term (at least a decade or more away), WestConnex’s Stage 3 is not; in fact Stage 2 is due to start construction this year, and will be built to link directly into Stage 3 when it begins construction in 2019.

WestConnex is, if anything, inevitable; the need for additional road transport linkages in Sydney’s inner west (and particularly along Parramatta Road) were identified years ago. However it has taken years to get to this point, where building is being fast-tracked due to necessity, particularly in the case of the New M5. The state and federal governments must supplement the developments with public alternative transport options, and not allow WestConnex (and especially the M4 East), require duplication just over a decade from now.

interesting. Melbourne needs even more work I’d say!

Standby for some Melbourne posts, coming your way soon! 😀

Thanks for reading 🙂

Far out… fascinating post, actually something I have never thought about before.

Hehe… thanks for reading – a bit of a departure from what I usually write… but something of interest to me 🙂

That’s a nice plan, I must admit. Fingers crossed everything goes well. You must be so excited about it!

It’s a huge project – it will be interesting to see how it affects Sydney! Thanks for reading, Agness 🙂

One thing that is not being considered is the impact of driverless cars. They are already happening, and the adoption of the next ten years could be similar to the way smartphones have replaced chunky mobiles.

Some of these new roads may well be totally unnecessary in the near future (from a technological point view not a Green Anarchist. Although that does tempt me!)

That’s true… although I’m looking forward to driving my car on the roads when they’re empty, then :p Thanks for reading 🙂