Experiencing Hiroshima

Hiroshima is a name synonymous with tragedy. What was once just another secondary city in Japan was catapulted to infamy on 6th August 1945 when it was devastated by the world’s first nuclear attack.

So notorious has the bombing become that it overshadows much of what Hiroshima is today; a modern, functioning Japanese city with a thriving arts scene; a jumping off point to the stunning Miyajima Island; and with an international airport, an entry point to the southern end of Honshu.

Despite these assets, Hiroshima today is undeniably shaped by the horrific events that unfolded that summer morning, as I was to find out on my recent visit there.

Hiroshima skyline by night

As if to emphasise that Hiroshima is influenced, if not defined, by the bombing, the city centre’s visage is dominated by the A-bomb dome. The Ōta River flows past the peaceful parks, and a small cluster of corporate buildings has sprung up further downstream. However the parks aren’t so much peaceful as they are eerily sombre – for they are dotted with memorials of the bombing.

The A-bomb dome (in Japanese called Genbaku Domu), officially known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, was once the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. Completed in 1915, it was designed by a Czech architect, and built from steel, concrete and stone.

After the detonation of the bomb, the A-bomb dome was one of the few buildings left standing. The bomb exploded 600 metres above the ground, above a point 150 metres to the east of the A-bomb dome. The building directly beneath the explosion, the Shima Hospital, along with everyone inside, ceased to exist at the moment of detonation. Everyone inside the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall were also killed instantly. In total, 70,000 people were killed by the initial blast.

Twisted metal at the A-bomb dome

Visiting the A-bomb dome today is an emotional and dissonant experience. The calm of the peacefuly flowing river, the solitude of the pretty park, and the quiet reverence of the visitors collide almost poetically with the jarring horror of the building. Local volunteers quietly fold colourful origami cranes, inviting visitors to join in, while just metres away the naked, twisted steel girders of the building tell their grotesque story. I can understand how some people find it strangely peaceful, but I found it deafening.

Folding paper cranes at the A-bomb dome

Across the river is the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. This is where the story comes to life, and some of the simply heartbreaking stories are told. Make no mistake, this place is not for the faint of heart, but then nor should it be avoided – it’s important that one witnesses the terrifying depths of human depravity, laid bare. The museum features, among other items, a wooden sandal bearing with an ashen footprint; the wearer was 13-year old schoolgirl Miyoko whose body was never found.

Miyoko’s sandal

Another gruesome exhibit are the fingernails and skin shed by high school student Noriaki Teshima; the heat from the blast caused much of his skin to melt off, and he died the following day.

Skin and fingernails of Noriaki Teshima

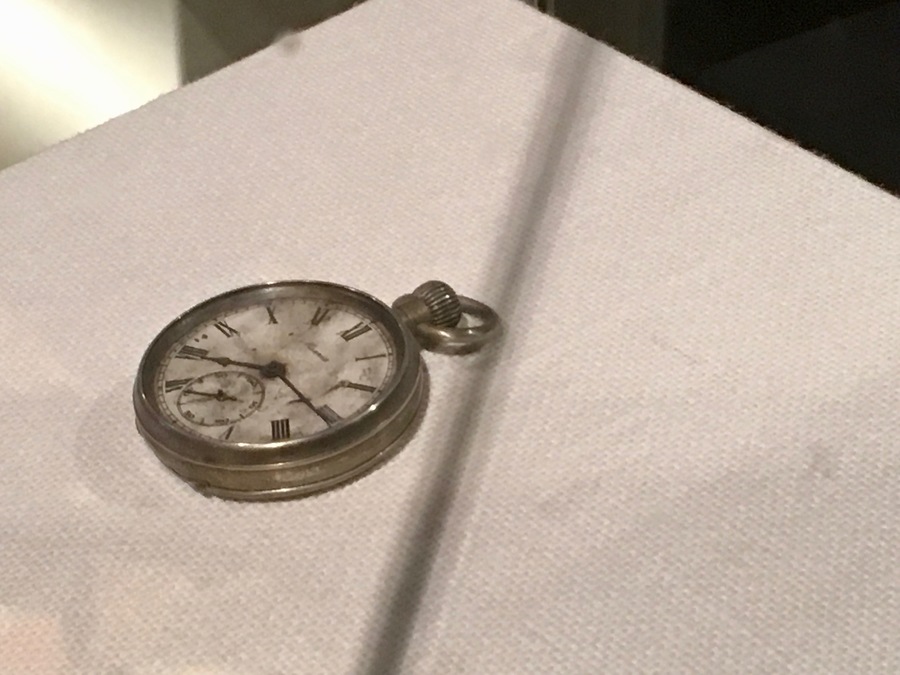

There’s the pocketwatch stopped at 8:15am, the exact moment of the blast; its owner was never found. The reconstructed porch of the Hiroshima post office bears a mark; the place on which a man was sitting and waiting for the office to open. The man vaporised in the heat, and all that’s left of him is the shadow his melting body cast as the bomb’s explosion blanched the surrounding stonework.

Steps of the Hiroshima Post Office – note the shadow stained on the stonework

Such is the gravity of the exhibits in the museum that I heard at least one visitor sobbing as she viewed them. If the stories of the bombing itself aren’t enough, then seeing the real exhibits before your eyes brings them to life. A real window pane stained with black raindrops is used to introduce the fact that some hours after the bomb, after the mushroom cloud had reached the upper atmosphere, black rain fell from the sky.

With all water supplies in the city evaporated, the desperate survivors opened their mouths to drink the deadly rain, probably unaware that the water was coloured with the radioactive ashes of their cityfolk. Up to another 90,000 people would die by the end of 1945 from the effects of radiation, or injuries sustained on the day itself.

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall

Throughout the rest of the park are various other memorials; The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims is a solemn, subterranean place for quiet reflection.

Cenotaph for Korean Victims

The Cenotaph for Korean Victims pays tribute to the up to 45,000 Korean nationals who were present in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing. The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound is a grassy knoll that contains the ashes of the 70,000 people who died at the moment of detonation, and therefore were never identified.

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

However for many the most moving memorial is the Children’s Peace Memorial. Shaped like a child with outstretched arms, this is where the thousands of origami paper cranes arrive every year.

Children’s Peace Monument

A Japanese tradition holds that a person who folds one thousand paper cranes will have one wish granted. When schoolgirl Sadako Sasaki was diagnosed with bomb-related leukaemia, she began a quest to fold the required number of cranes. Her wish was to be a world free of nuclear weapons. She succumbed to her illness at the age of twelve, apparently having folded just 644 cranes. Her schoolmates folded the remaining 356 to be buried with her body. Again, expect tears at the Children’s Peace Memorial, especially if a school group is visiting to contribute their latest set of folded cranes to the exhibition.

Cranes at the Children’s Peace Monument

In the centre of the park is the Peace Flame, importantly, not an eternal flame; this one is designed to be extinguished if and when the world is rid of nuclear weapons.

Hiroshima is no doubt a great city beyond the Peace Memorial Park, however it would be wrong to overlook the reality of Hiroshima today. Hiroshima isn’t completely defined by the events of 1945, and nor should it be, but it’s safe to say that its recent history has played the biggest role in its contemporary profile around the world.

So while Hiroshima isn’t simply a product of the atomic bombing, it’s no doubt a beacon of hope in the practice of remembering what happened, and the efforts to prevent it from ever happening again.

So interesting Tim

Thanks for reading, mum xx

the way Hiroshima has risen from the ashes to be such an amazing, welcoming and vibrant city is an incredible story!

True – it’s a wonderful place.