It was the late 1970s, and after decades of relative peace, Afghanistan stood at a precipice. The voices of nationalists, communists, monarchists and theocrats were getting louder, each trying to drown the others out, while in a small village to the north of the country, Soviet archaeologist Victor Sarianidi began uncovering golden artefacts from a 1900 year old civilisation. Crowns, sceptres, hairpieces, knives and coins were laid out across six graves, presumably once placed upon a body for passage into the next life. In all, 20,000 pieces were discovered, mostly containing gold, but some also adorned with turquoise and/or lapis lazuli.

Throughout 1979, Sarianidi worked on the site called ‘Tillya Tepe’ (Persian for ‘Hill of Gold’), while the dogs of war strained at their leashes. Finally, on Christmas Day 1979, his time ran out; the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and the country descended into chaos. While Sarianidi fled back to Moscow, his finds at Tillya Tepe were moved to their logical home in the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul. Their fate was unknown, but somewhere between the withdrawal of the Soviet army in 1989, and the savage civil war in the 1990s they disappeared. Impoverished and desperate, the Taliban administration looted what was left of the museum in 2000, and when the world’s attention was thrown back on Afghanistan the following year, the building was found to be almost bare.

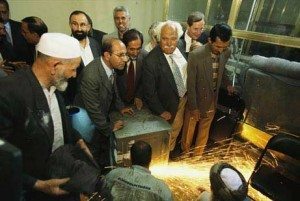

In 2003 Sarianidi, then living in Greece, received a call informing him that large welded chests had been discovered under the Kabul Museum, and inviting him to be present in the Afghan capital when they were opened. He flew to Kabul, a shell of how he remembered it from the 1970s, and the chests were prized open. Inside was a wealth of jewellery, but the question still remained whether it was in fact Sarianidi’s find from 1979. Picking up one piece, a smile slowly spread across Sarianidi’s face. He confirmed that the gold in the chests was from the Tillya Tepe dig, known as ‘Bactrian Gold’, that he had uncovered all those years before. Holding out the piece in his hand, Sarianidi explained how it still showed evidence of a small repair he made to it in 1979, the last time he had seen it.

The gold from Tillya Tepe, once part of a kingdom known as Bactria, is remarkable not only for its survival, but for its intentional preservation during decades of conflict and pillage. Since 2003 it has been reinstated in the National Museum of Afghanistan, however it regularly tours other museums, and a selection of the find is now on display at the Melbourne Museum as part of the Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures exhibition. Other displays include evidence of a fantastical civilisation at Tepe Fullol in the Bronze Age, around 4000 years ago, and uncovered in the past century. The ancient Hellenic influence of Alexander the Great can be seen in the second section of the exhibition, centred around a 2100-year old city in ruins near the Afghanistan’s modern day border with Tajikistan. Artefacts such as a sundial point to the technology of the age, while Greek-style turreted roofs suggest a blending of cultures.

The final section of the exhibition focusses on the ancient city of Begram, which might be more familiar to contemporary readers as the site of the United States’ Bagram Air Base. In Begram, a vault with tiles, sculptures, tools, glasses, platters and household ornaments (including a novel stone fish pond) was discovered, untouched since it was sealed shut 1700 years ago. The presence of foreign militaries in Bagram today, just kilometres from the location of the centuries-old vault, is testament to the massive and terrible tumult that has scarred Afghanistan through the centuries. The cosmopolitan nature of ancient Afghanistan is a theme of the exhibition, as it explores the days of the silk road where Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Persians and Europeans would all mix relatively peacefully, representing the earliest and some of the most successful years of globalisation.

The gift shop outside the exhibition is excellent, selling an impressive variety of of books, CDs, teapots, urns and ceramic arts, all passionately Afghan in style. Directly ahead of that, and back at the beginning of the exhibition is the Afghanistan cafe, where one can enjoy a delicious snack with a modern twist on Afghan cuisine; think orange, cardamom, rosewater and pistachio cake, or qibili pilau, a tangy lamb stew served with rice. Vegetarians aren’t forgotten either, with leek and lentil sandwiches served with that central Asian staple – yogurt. Wash it all down with some Afghan tea, or finish off with one of the tasty square shortbreads, not particularly Afghan, but iced to resemble an intricate ceramic tile.

However the overarching theme of the exhibition is one of endurance and preservation, and not one chance is missed to recognise the Afghans who saved Afghanistan’s history by, for instance, burying the Bactrian gold away from prying eyes. Despite having to discover the gold twice, Victor Sarianidi would have been thankful that the artefacts had been hidden. At the end of the exhibition is the same Afghan proverb which is now emblazoned across the front of the museum in Kabul; a nation stays alive when its culture stays alive.

Details

Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures is showing at the Melbourne Museum until the 28th July 2013. It is expected to appear at the Art Gallery of Sydney in 2014.

Where: Melbourne Museum, at 11 Nicholson Street, Carlton, VIC

When: Daily, 10am – 5pm

How much: $24 adult, $16 concession. The ticket includes admission to the Melbourne Museum (usually $10 per adult). The audio guide, an additional $7, is well worth it.

How long: put aside between one and two hours for the Afghanistan exhibition, while the rest of the museum could easily fill a day.

Book tickets online here.

Amazing post, truly insightful. After reading it I could go there and already know a background story. Yeah, I was I was in Melbourne to tour the museum. Keep it up Tim !

Thanks Cez!!! I loved the exhibition, and I love that part of the world – I just wish it was more accessible to outsiders. I hope I can share some of it through writing like this – there is so much history, and we have lived through some of it in our lifetimes!!