Sometimes in lives our imaginations are inexplicably piqued by otherwise unremarkable circumstances. It happens when one is walking home at night, and through the darkness a sliver of light catches one’s eye. We deviate from our well-trodden paths to investigate; through the bushes we see an open window, and inside, perhaps a child playing with his father, a family mid-argument, or a couple in the act of seduction. Our curiosity captivates us, wondering what story lies behind the scene, what trophies and scars of life the protagonists bear.

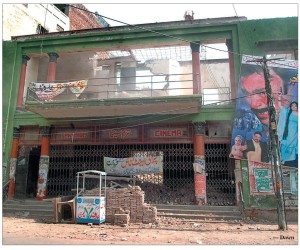

I was wandering through the Lahore’s fabled Walled City with a friend many months ago when I saw the rusted steel gates cordoning off what used to be the Tarannum Cinema. The shattered glass sign above the gate wore the name of the former building in red lettering, in both English and Urdu. Inside, the empty lot had been concreted over, save one corner where a small patch of grass was growing raggedly. There, a rake-thin man was draped in a shalwar kameez typically worn by Pakistani men. He was sitting in the shade provided by a neighbouring building, watching over two small goats as they grazed on the straggly lawn. Intrigued, I asked my friend what the story was. “It was an old cinema,” he told me, “a famous cinema – one of the oldest in Lahore”. Listening to his words, my intrigue grew. How could a supposedly well-known cinema with a long history have ended its life like this? It was a hot June day; the sun was slowly roasting us into submission, and we didn’t have time to stop – but I, or rather, the writer in me, knew that a return visit was inevitable.

Some months later, and in more agreeable weather, I returned with notepad in hand. I met with another friend of mine, himself an inhabitant of the Walled City, and familiar with the history and goings on of the area. We wandered through the narrow laneways between ramshackle houses and businesses, swimming through the terrifyingly intricate aromas which wafted from the open windows. When I casually told him about my quest to uncover the history of Tarannum Cinema, he chuckled. “What a story” he laughed, “this cinema has a long, very long history. It was named after a Pakistani singer – Malika-e-Tarannum Noor Jehan. Her name literally means ‘Queen of Melody, Light of the World’.” He went on to explain that there are many stories about the history of the cinema, but one tells that Noor Jehan once owned it…

On 21st September 1926, Allah Wasai was born into a Muslim family near Lahore in what was then British India. Legend has it that her family were involved in the dancing girl business in Lahore’s red-light district of Hiramandi – although no-one will actually confirm this. At a young age she moved with her family to Calcutta, to pursue her acting career, and it was there that she adopted her stage name Baby Noor Jehan. She was an instant hit – her precocious beauty captivated audiences, while her pure singing voice caught the attention of filmmakers. At the age of sixteen Noor Jehan relocated to the city of Bombay to work with director Syed Shaukat Hussain Rizvi, and the two married soon after.

Following the partition of India in 1947, Rizvi moved his business to Lahore in the new state of Pakistan. There, he and Jehan founded the pioneering Shahnoor Film Studios, which still stands today on Multan Road. The pair also invested in cinema halls, including the Novelty Cinema in the Taxali district of Lahore’s Walled City. Besotted by his beautiful young wife, Rizvi gave the Novelty Cinema to Noor Jehan as a romantic gift – a glamorous mark of the couple’s preeminence in the fledgling Pakistani film industry. As Jehan’s stature as a singer grew, the cinema would be named after her; Tarannum; ‘Melody’. At the height of its popularity, the cinema was one of the most popular venues in the city, drawing in crowds of joyous cinema-goers who would queue up, watch, laugh, sing, whistle and dance. The ethereal Malka Tarannum Noor Jehan would often grace the screen herself, a heroine to both her on-screen counterparts and to her adoring fans in films such as Dupatta (1952) and Mirza Ghalib (1961).

By 1954 Jehan and Rizvi divorced, but Jehan retained ownership of the cinema. Over the following years, scandalous rumours linked Noor Jehan to several celebrities until in 1959 she married actor Ejaz Durrani, nine years her junior. While married to Durrani, she gave up her career to raise her six children (three from her first marriage). By the mid-1970s, however, her relationship with Durrani had also come to an end. Noor Jehan saw out the rest of her days working as a playback singer, and singing patriotic tunes for the Pakistani military during their encounters with India. Throughout her career she received several accolades, including the Tamgha-e-Imtiaz (Medal of Excellence), one of Pakistan’s highest civilian awards. Noor Jehan passed away in Karachi on 23rd December 2000 after a long battle with illness. She continues to be considered one of Pakistan’s most talented performers.

My friend and I had finally reached the intersection of the Walled City where the Tarannum Cinema once stood. In the middle of the twist of roads stands a tall, narrow Ashurakhana, a community mourning house occupied by Shia Muslims during the occasion of Ashura. Autorickshaws spluttered past, and someone had set up a small stall in front of the Tarannum’s gate. The empty facade seemed even more neglected now that it had on my first visit – the additional damage to it seemed disproportionate to the duration of intervening time.

“So what happened to the cinema hall?” I asked. My friend replied that Noor Jehan had sold it during the mid-1990s in order to fund her medical treatment. “It was sold to an investor from Gujrat” he told me, referring to the Pakistani Punjabi city with a knack for producing savvy businessmen. “But by then, there was no business.” General Zia-ul-Haq’s iron-fisted ‘Islamisation’ drive in the early 1980s spelled the death of many Pakistani film studios, and the industry arguably reached its nadir in the 1990s. Many cinemas closed down as a result, and now only about eighteen of the original halls remain, as compared with over eighty in the 1970s. A near-ban on imported Indian films until 2008 depressed the industry even further – the Tarannum’s glory days were clearly behind it. “It closed about eight to ten years ago,” I was told, “and it just sat there until last year when it was demolished. They want to build a shopping mall there.” The site’s owner is apparently waiting for a development application to be approved. But for now, the site sits there vacated, unused, lonely, perhaps home to the ghosts of a golden era. The storied Tarannum Cinema, and its distinguished namesake, are no more.

Leaving Lahore’s Walled City and back on the bus home, the cinema lights were snapped on and the reel could be heard flapping behind the projector. Like waking up from a surrealist dream, my experience in the Walled City now reverberates around my imagination. I arrived home, and type ‘Tarannum Cinema’ into Google, just to see if anything else could be added to the story. The first result I find is a newspaper article published a day after the building was razed – 1st July 2012. Shockingly, the story reported by Dawn seems to refute some of the tale which had left me so spellbound. For example, the site’s owner Saleem Jora says he bought the cinema forty years ago, before it was renamed Tarannum. However the article also reports that he doesn’t remember much more about the history of the building. It seems that like so much of life in Lahore’s beguiling Walled City, it’s difficult to know where the reality ends and fiction begins. Perhaps, like Noor Jehan and her illustrious yet tumultuous life, the secrets of the the Tarannum cinema are now destined to survive only in legend.

Published in association with Cinema Stories.

0 Comments